A byte-size chunk of Python basics

Python fundamentals guide that | s l a p s |. Read docs, help() functions, and practice, practice, prActIce!

Skip the description, let’s get to the code!

Hello world

Many programmers It is not enough to reach for the brass ring. You must also enjoy the merry-go-round - Julie Andrews know how to code in Python

It is not enough to reach for the brass ring. You must also enjoy the merry-go-round - Julie Andrews know how to code in Python Where can I squanch because

Where can I squanch because Do we have a based god? it has

Do we have a based god? it has 10x your productivity with git aliases like ‘ga’ for ‘git add’, ‘gs’ for ‘git status’… fairly

10x your productivity with git aliases like ‘ga’ for ‘git add’, ‘gs’ for ‘git status’… fairly Jojo says Phantom Assassin is not balanced modern

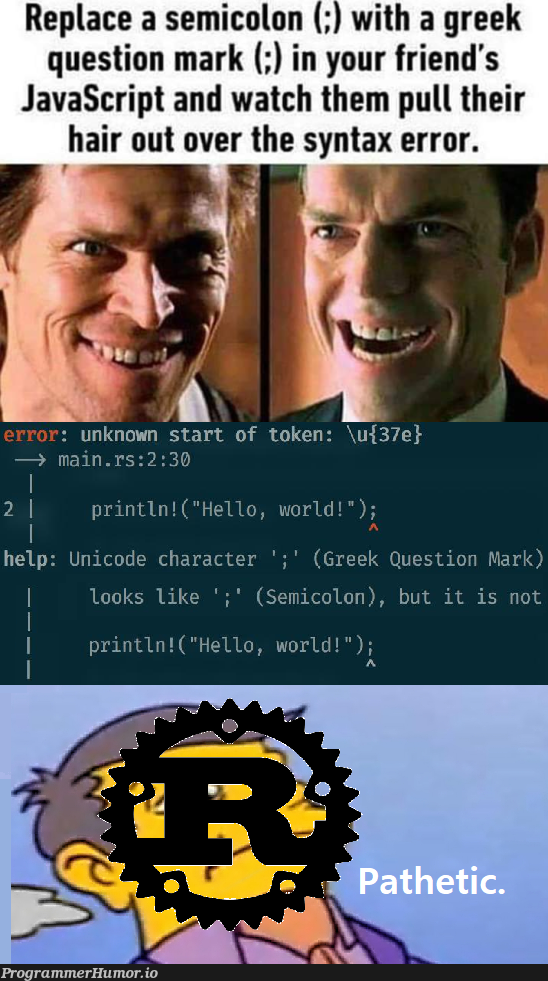

Jojo says Phantom Assassin is not balanced modern Modern work strategies often involve computer technology in some way or another syntax

Modern work strategies often involve computer technology in some way or another syntax Syntax is more interesting and difficult the deeper you go to learn, a full

Syntax is more interesting and difficult the deeper you go to learn, a full eh, give or take…byte me. object

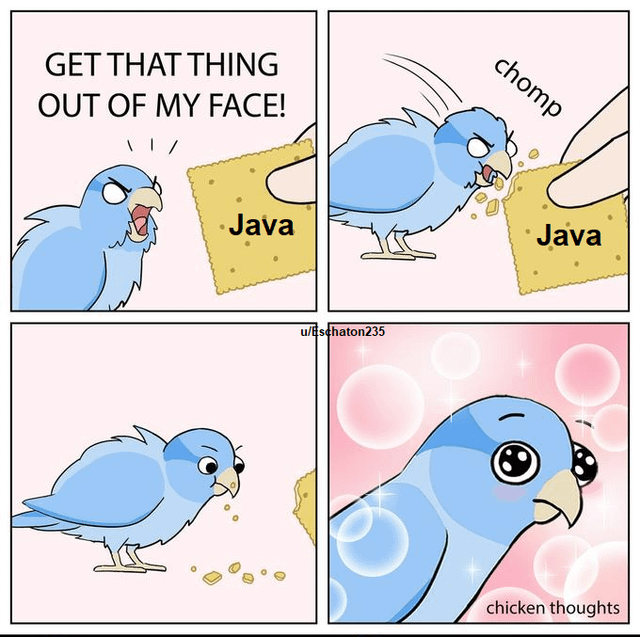

eh, give or take…byte me. object Java is a OOP-focused enterprise language by Sun Microsystems-oriented

Java is a OOP-focused enterprise language by Sun Microsystems-oriented MFW whole class shows up in jammy-jams programming and inheritance

MFW whole class shows up in jammy-jams programming and inheritance OOP (1990-2020) is a paradigm with roots in CompSci pragmatism stack

OOP (1990-2020) is a paradigm with roots in CompSci pragmatism stack AI tools arent always positive, web

AI tools arent always positive, web www.com serversWhen you need the job…, and other

www.com serversWhen you need the job…, and other Moth loves LAMP modern

Moth loves LAMP modern Some might say…. tooling

Some might say…. tooling /home improvement.

/home improvement.

If you want Everybody's talking about the good old days. Know what I'm saying? Take you on this lyrical high real quik. to read more

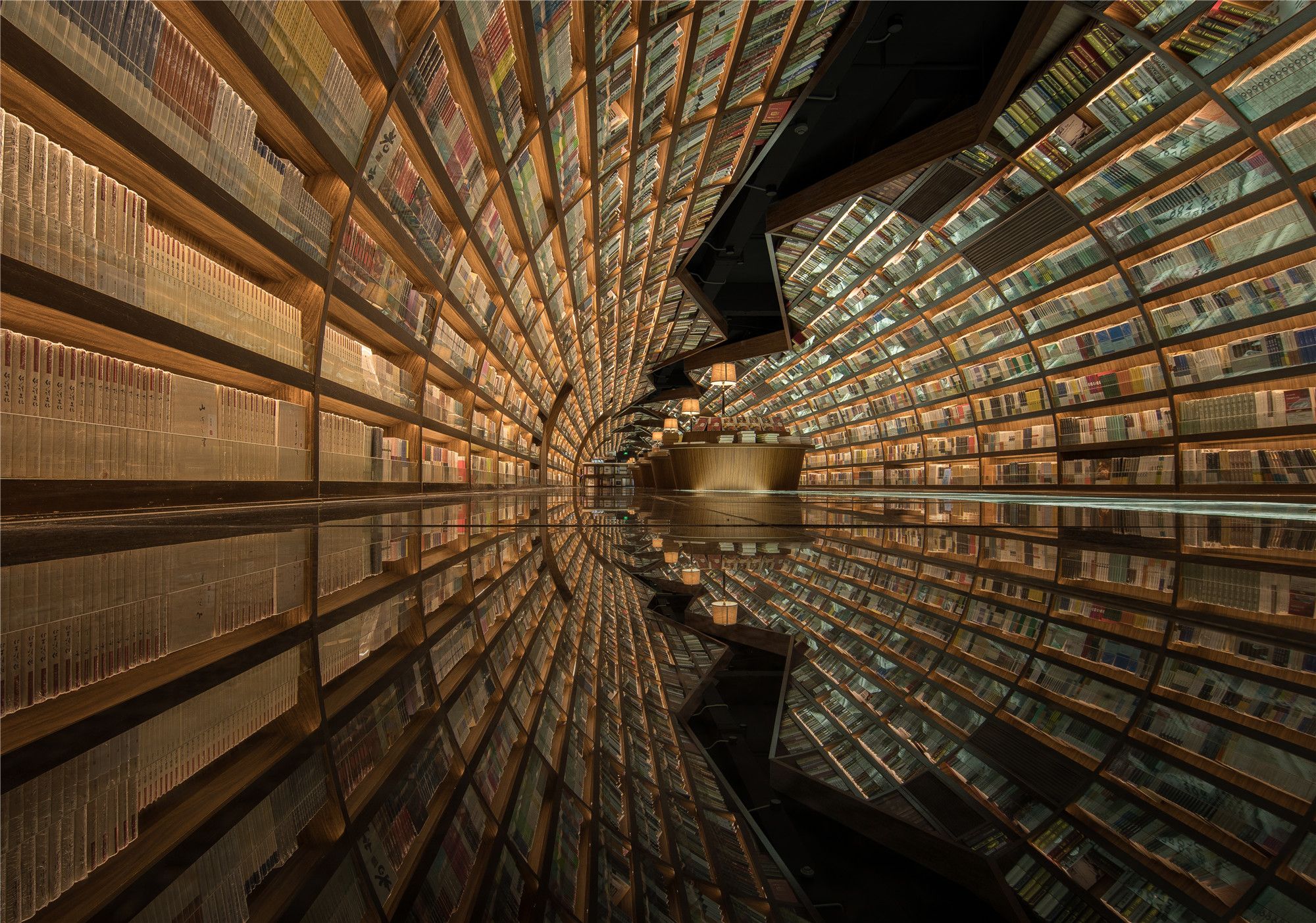

Everybody's talking about the good old days. Know what I'm saying? Take you on this lyrical high real quik. to read more Yangzhou Zhongshuge - X+ living, check out

Yangzhou Zhongshuge - X+ living, check out it's not complicated. Avoid stash. Try to rebase. In case of emergency break glass and force push. https://python.org or the Wikipedia page on the language to learn more

it's not complicated. Avoid stash. Try to rebase. In case of emergency break glass and force push. https://python.org or the Wikipedia page on the language to learn more Chicago Public Library - SOM about its history

Chicago Public Library - SOM about its history Smithsonian Museum of Natural History - D.C. and use

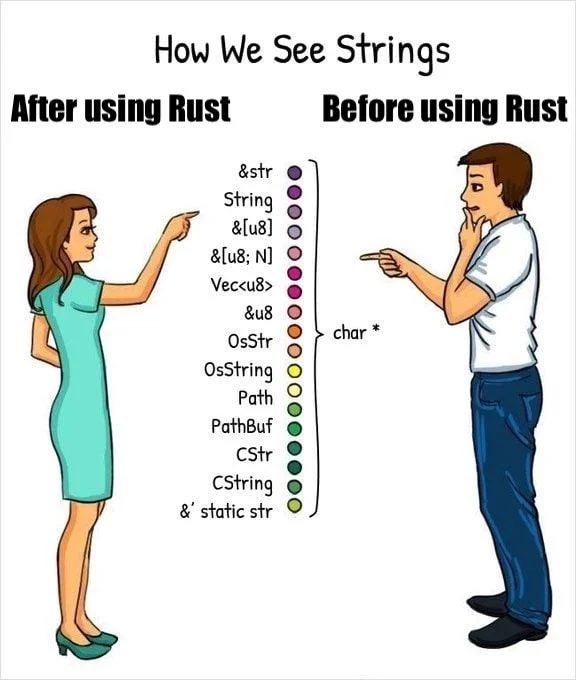

Smithsonian Museum of Natural History - D.C. and use Data types are part of what makes rust impossible to use. cases

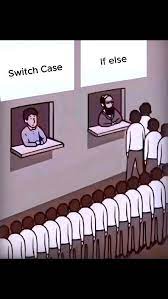

Data types are part of what makes rust impossible to use. cases Switch/match have concise syntax. That is all..

Switch/match have concise syntax. That is all..

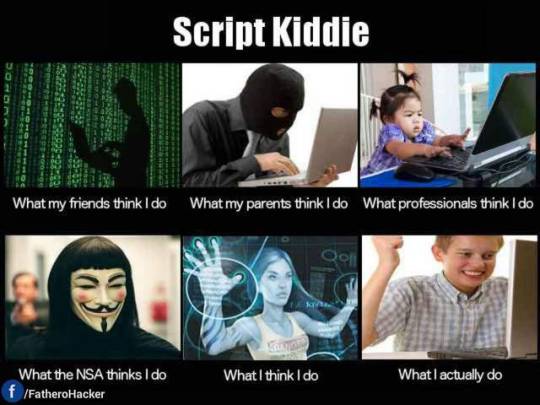

We Hello, fellow insert field here.‘re going to skip ahead

Hello, fellow insert field here.‘re going to skip ahead Child labor laws are ruining this country /s a bit

Child labor laws are ruining this country /s a bit Wonder what kind of content I should try to make? and get

Wonder what kind of content I should try to make? and get wAkE mE up… to

wAkE mE up… to I mean… im13andthisisdeep.png building

I mean… im13andthisisdeep.png building Shhh.. HO! modern

Shhh.. HO! modern Everyone’s a critic scripts

Everyone’s a critic scripts humbleflag and describe features

humbleflag and describe features Writing tests allows teh dev to specify what code quality means. The opposite is just testing in production. that python CLI tools should have

Writing tests allows teh dev to specify what code quality means. The opposite is just testing in production. that python CLI tools should have Is DRM art? for you

Is DRM art? for you Costs a buck ‘o five to get ahead

Costs a buck ‘o five to get ahead “You humans think greed is just for money and power, but everyone wants something they dont have” of the competition

“You humans think greed is just for money and power, but everyone wants something they dont have” of the competition With all my fart. in modern AI and data science related

With all my fart. in modern AI and data science related It's not so much that the rich are bad. It's that workers rights are often at odds with laissez faire markets. And, there are some bad actors. roles

It's not so much that the rich are bad. It's that workers rights are often at odds with laissez faire markets. And, there are some bad actors. roles Diablo 2 represents some of the best online gameplay I've experienced..

Diablo 2 represents some of the best online gameplay I've experienced..

Prerequisites

This tutorial Building strategies are my favorite genre. I’m in a moba phase because of the rng…. assumes

Building strategies are my favorite genre. I’m in a moba phase because of the rng…. assumes Always test before force pushing. Except when you dont. Then, just dont. you have some basic

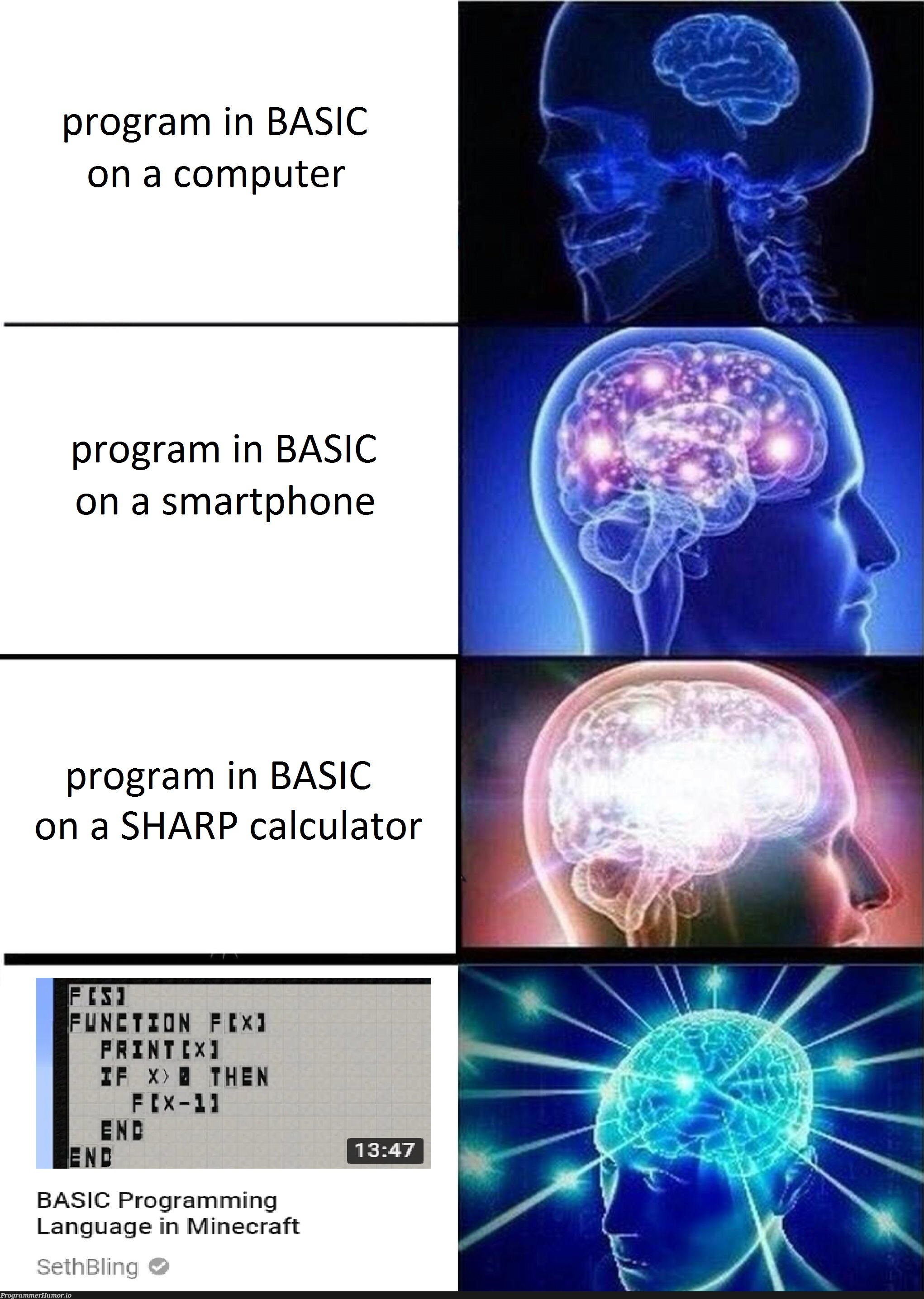

Always test before force pushing. Except when you dont. Then, just dont. you have some basic BASIC (Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) was a language invented in the 60s for non-scientists. The Microsoft BASIC is the most popular version used in modern times. knowledge

BASIC (Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) was a language invented in the 60s for non-scientists. The Microsoft BASIC is the most popular version used in modern times. knowledge Star Trek was a great show. Recommended. of programming

Star Trek was a great show. Recommended. of programming Coding is just another tool to master. Nothing more. A lot, a lot less than what people make it out to be. and the Linux or MacOS

Coding is just another tool to master. Nothing more. A lot, a lot less than what people make it out to be. and the Linux or MacOS Just buy a new _/OSX

Just buy a new _/OSX Apple makes decent hardware but is anti-repair POSIX shell

Apple makes decent hardware but is anti-repair POSIX shell Please, it's not recycling. It's stewardship of spaceship earth. Please think responsibly. environments

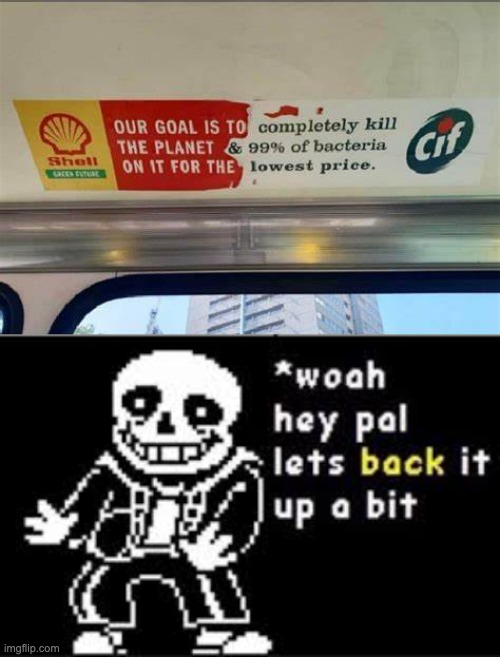

Please, it's not recycling. It's stewardship of spaceship earth. Please think responsibly. environments Biodiversity bad, investors sad, cleaning up my mess is not very rad.. These skills

Biodiversity bad, investors sad, cleaning up my mess is not very rad.. These skills Teamwork makes our dreams smirk are fundamental

Teamwork makes our dreams smirk are fundamental Check ma’ autographs for invoking

Check ma’ autographs for invoking Invoker is a DotA2 hero with huge abuse potential. the Python

Invoker is a DotA2 hero with huge abuse potential. the Python The Python and the dog found their unlikely happiness. Bob's Burgers, S3E18. interpreter

The Python and the dog found their unlikely happiness. Bob's Burgers, S3E18. interpreter Language, syntax, translation on your scripts

Language, syntax, translation on your scripts If you're on the phone, don't be a jerk., CLI tools, server applications, and more. Such skills

If you're on the phone, don't be a jerk., CLI tools, server applications, and more. Such skills Many typeies, much wow. include invoking

Many typeies, much wow. include invoking We like to party (for mmr) programs from bash

We like to party (for mmr) programs from bash There's treasure everywhere!/fish

There's treasure everywhere!/fish Jesus, thank you for making loaves and fishes. Happy Easter. ojala que mas de nada para todos./zsh

Jesus, thank you for making loaves and fishes. Happy Easter. ojala que mas de nada para todos./zsh Vote for paidro/csh

Vote for paidro/csh She sells sea shells shells

She sells sea shells shells I'm not really into class war. But I am when I'm underemployed and skills are stagnating. and terminal

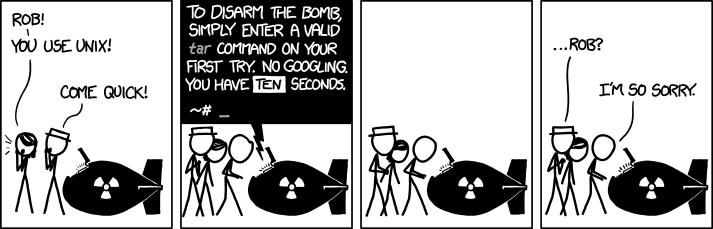

I'm not really into class war. But I am when I'm underemployed and skills are stagnating. and terminal Early telecom is incredible. evironments, convention

Early telecom is incredible. evironments, convention XKCD remains a favorite of mine. Thanks KS and D for this. of standard-input

XKCD remains a favorite of mine. Thanks KS and D for this. of standard-input How do you read stdio?/output

How do you read stdio?/output My brain runs on anxiety, paranoia, and social isolation. Thanks Delaware. and piping outputs to sequential

My brain runs on anxiety, paranoia, and social isolation. Thanks Delaware. and piping outputs to sequential Yoda knows the unconventional sequences. I do not. Do not. commands, decompressing

Yoda knows the unconventional sequences. I do not. Do not. commands, decompressing Ever hear of a .tar bomb? files, redirection

Ever hear of a .tar bomb? files, redirection Bby yoda redirects you to somewhere else. Go away. of standard output

Bby yoda redirects you to somewhere else. Go away. of standard output Breaking badge… or standard error

Breaking badge… or standard error What is the difference between std deviation and std error? (Hint: also called standard error of the mean) streams

What is the difference between std deviation and std error? (Hint: also called standard error of the mean) streams Hi sauce its vchat to different files, and a feeling or familiarity

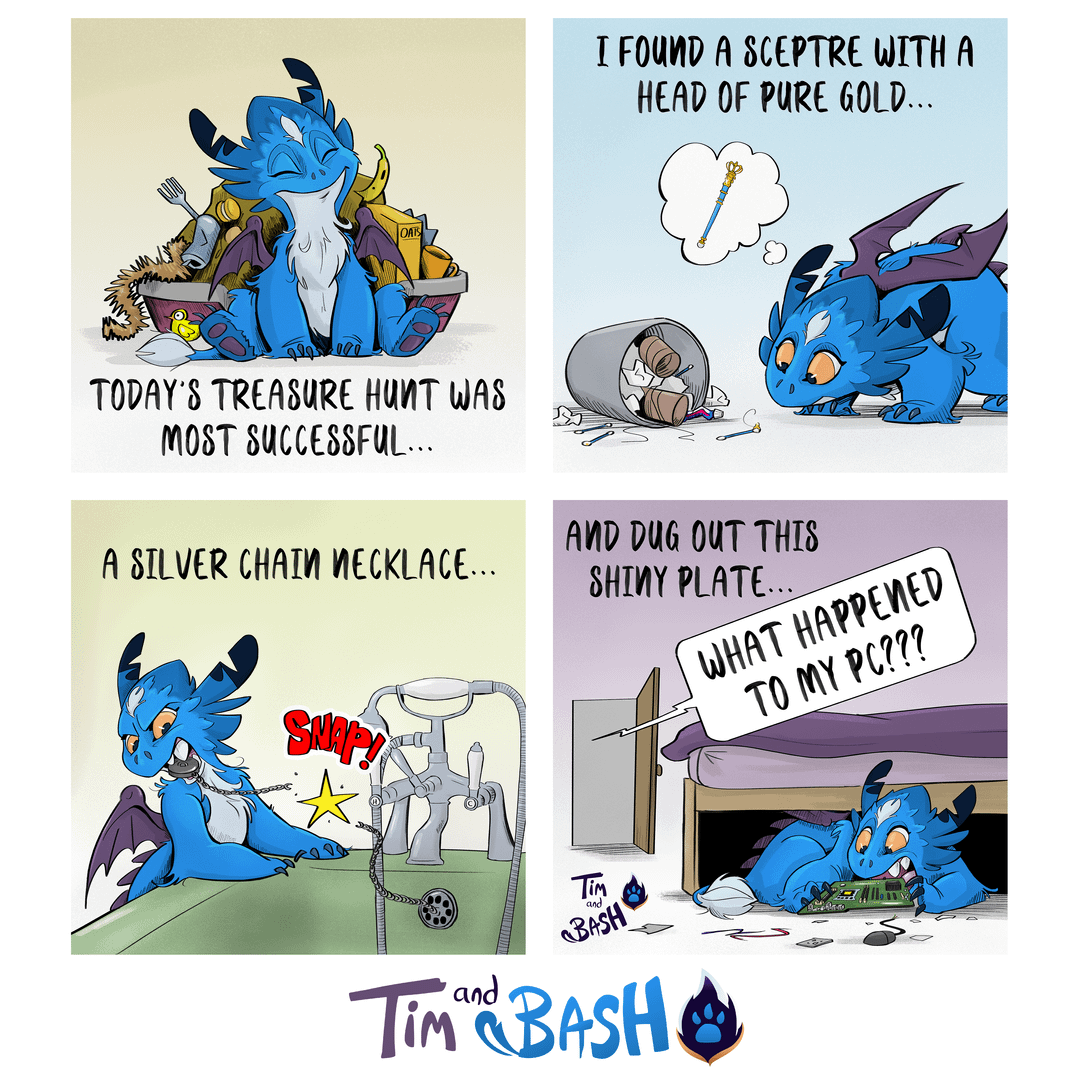

Hi sauce its vchat to different files, and a feeling or familiarity Tim and Bash on vengeance and humiliation concerning easy-to-use tools and how they handle flags, parameters, logging, arguments, etc.

Tim and Bash on vengeance and humiliation concerning easy-to-use tools and how they handle flags, parameters, logging, arguments, etc.

Second, this tutorial assumes They see me trollin' some

They see me trollin' some Assumptions are where its at familiarity

Assumptions are where its at familiarity idk what are relationships like for you with the Python build chain, which revolves around PyPI and PEP standards and includes knowledge of the

idk what are relationships like for you with the Python build chain, which revolves around PyPI and PEP standards and includes knowledge of the pip command-line tool. Specific additional files in your codebase may be required for installation via conda (not covered here) and pip. Examples of necessary files are setup.py, pyproject.toml, requirements.txt, Pipfile, .python-version, and setup.cfg (usually optional). You may also require conventional plain-text files such as README.md, LICENSE.txt, and .gitignore.

Additionally, many new users might be overwhelmed with the variety of file formats available on Linux, and how using the wrong file as input may result in parsing errors and program crashing. Most files (such as .fasta or .sam files in bioinformatics) are simple plain-text without compression or encryption. However, due to the file structure, many plain-text categorized files are incompatible with tools that accept plain-text as input. Play around with different formats in your area with inspection via your IDE or editor, or the cat and head commands to see what the format specification looks like (how the file looks in terms of sequential lines, columns, separators etc.).

Okay! Let’s get to the code!

How do I design a good Python package?

First things first, you should plan out your desired command line tool most likely from the top down. For example, you might want to write a tool that has multiple scripts that can be run from a unified environment. e.g.: mypackage subcommand --input input.txt

By planning the interface first, rather than the functions and modules/classes required, it allows the developer to create elegant and easy to use scripts and packages that require less guesswork for the user to use and/or contribute to development.

Standard input/output conventions

Many tools in MacOS/Linux environments revolve around the conventions of plain-text standard input and output. You may, for ease-of-use and intuitive invocation reasons, decide to accept either a ‘named argument’ (e.g. mypackage subcommand --input input.txt) or a ‘positional argument’ (e.g. mypackage subcommand input.txt) for the primary input, typically data stored in a file, often simple plain-text.

As it follows, standard output is often preferable for the primary output of text, formats, and information that can be captured with shell stdin/stdout stream redirection. For this reason, it is helpful to separate information for the user into stderr stream, and actual program output and file data exclusively to the stdout stream.

Because programming is not my area of first knowledge, it took me some time to get the intuition about how to separate logging, program output and statistics, and data output into stdout and stderr streams, such that a valid or parseable table (

.tsv,.csv) is produced separately from necessary information for the user, such as statistics, run-time, and other metadata.

--verbose, -v, -vv and logging

Another area that requires some design effort is the system of logging what the program is trying to do, at various levels of verbosity. Conventions for logging often include the date/time, the log-level, and the area of code emitting the log statement.

Without good logging, many poorly designed programs may crash or choke on bogus user input without warning or solution, and result in wasted time for the user, poor opinions about the program for the user, and make you seem clueless as a developer.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution for log formatting and log inheritance patterns, especially when logging from other modules conflicts with global verbosity settings.

In other words, develop robust logging habits and sensibility concerning log-level, debug flags, and other stderr oriented habits for developing, debugging, and compartmentalizing your log statements from user-interface text, which may/should also be on the standard error stream, to differentiate it from output data, which may need to be piped from one command to the next.

Error handling

Another great way for beginners to make their Python packages more robust is to include assertions and type-checking throughout their codebase. If you have a function, the first thing to do is validate the types of the arguments you’re passing through. If the developer has the chance to pass through invalid data from the argument or elsewhere in the codebase, your type checking Tuh-mater will let you know at least that the functions you care about will not accept invalid inputs.

Tuh-mater will let you know at least that the functions you care about will not accept invalid inputs.

But why? Why do I need to validate the types of arguments I’m passing through?

The first reason, is for yourself. As your codebase gets more complex, getting a cryptic type-related (not necessarily a TypeError) exception from a third-party module may give you headaches. It takes about 5 seconds to copy paste a error message template to handle the if statements, conditions, at which you would want your function to throw an error. In this case, the ‘user’ is you! If you’re making a module for others to import then you’ll want to do this anyway.

Strong error messages may look like the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

def myfunction(a: int, b: str, named:str=None):

if type(a) is not int:

raise TypeError("module.myfunction expects an int as its first positional argument")

elif type(b) is not str:

raise TypeError("module.myfunction expects a str as its second positional argument")

elif named is None or type(named) is not str:

raise TypeError("module.myfunction expects the 'named' keyword argument to be a str")

# ...

print("Done")

myfunction(1, 'hello world', named="foo")

The first line defines a function named ‘main’ with the reserved keyword def. This def keyword is a special Python syntax for defining Python functions. The name of the Python function follows the def keyword, followed by parentheses which enclose arguments to the function, their type-hints, and in the case of the keyword argument ‘named’ assigns a default value of None.

In the example, a Python version 3+ syntax called the ‘type-hint’ is included, but that’s beyond the scope of this blog post. In short, the first argument ‘a’ follows the opening parenthesis, with a colon followed by another keyword ‘int’. Note the syntax highlighting differences between def, myfunction, ‘a’, and int. The function name preceeds the parenthesis in the function definition line. ‘a’ represents a variable that will be available in the function body, provided by the user in the last line of the example.

The int keyword does not do anything. Isn’t that weird? It’s merely a notation at this point to remind developers what type is expected for the positional argument ‘a’. I refer to arguments as positional as their sequential order in the function definition. ‘a’ should be an integer, a whole number (0,1,2,… etc.). They would also be present in the *args splat. However, named would be in the **kwargs splat.

‘b’ on the other hand is a string argument, ASCII or UTF-8 characters enclosed by single -> ' or double -> " quotation marks.

The last argument is not positional, and is refered to as a keyword argument. Keyword in this context refers to passing the argument by named="something" with an equals sign, not to be confused with my earlier reference to reserved keywords in the Python language such as def, int, and str.

Now that we’ve seen an example of Python code and we have described the use-case of defining and calling a function, let’s move on to a self-contained example that the reader may copy and paste into a file, make the file executable with ‘chmod +x myprogram.py’, and call the program with ‘python3 myprogram.py’.

How do I write a Python program?

Let’s start with some simple code. Consider the following Python script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

#!/bin/env python3

import argparse

def main(args):

"""

This is *your* main function, and does exactly two things.

The rest of the code in this example is boilerplate or related to parsing arguments.

First, the arguments parsed by the built-in argparse module, which ships with all versions of Python,

are printed to the console by default.

Second, the string 'hello world' will be printed to the console.

That's it! Now you're starting to write Python programs!

"""

print(args)

print("hello world")

"""

The following routine has some confusing boilerplate, like 'if __name__ == "__main__":'

But don't worry, in a little bit, most of this stuff will make sense.

"""

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("--required", type=str, help="This argument is required and takes a string as input", required=True)

parser.add_argument("--flag", action="store_true", help="This is a flag argument, which stores a 'True' bool when added")

args = parser.parse_args()

# Main routine

main(args)

In the example above, we have two primary parts. The first is the function main, a simple pair of print statements. In this case, we only have one argument: args. This will be an argparse object, again something beyond the scope of this blog post.

When you run the program, you’ll see some notation that packages all of the arguments to the script in a unified object for convenience.

The second part is this awkward if __name__ == "__main__": thing. Basically, the Python interpreter looks for this notation by default to describe what must be run first, in order to call additional functions and class methods etc. to produce program behaviors. Inside this block of code we have a few statements that allow the argparse module, that is built-in to the Python interpreter’s standard library, to define arguments that can be captured by the program and the interpreter to pass arguments through to the user’s main function, with its print statements.

What is a variable?

Variables and constants can be defined in Python to capture return values from functions that can be manipulated and passed to other functions, printed, or used otherwise. Check out this simple example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

CONSTANT = "Dont use globals and constants unless you need to. Variables do just fine, most of the time."

myvariable = 8 # int

myvariable = "now its a string" # str

othervariable = 0.4 # float

nothing = None

convert_a_float_to_a_str = str(othervariable)

Variables can be any valid Python type, such as int, float, str, None, and more.

What about conditional statements, or the if operator?

At times, you may want to check your variables to decide what to do next. Enter the ‘if’ statement. You can use ‘if’ statements to produce branches of code that do different things. If you have the time, continue reading to learn about the use case for if, else, elif, and match statements.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

if myvariable == 8:

print("This should be True, if your 'myvariable' is indeed 4+4.")

elif type(othervariable) is float:

print("""This should also be True, because there is a decimal in this variable's

definition, making the number a floating-point number.""")

else:

print("Something may have gone wrong.")

raise RuntimeError("Either myvariable's defintion has changed, or othervariable has changed")

match myvariable:

case 8:

print("The variable is still 8. Try changing the variable's definition to something else...")

case 0.8:

print("Now we have a real valued 'myvariable', not just the original integer")

case _:

print("Underscore '_' represents a generic catch-all value, much like the 'else' statement")

Use Python’s loop functions to do awesome things on lists!

There are two primary functions to do things in sequence or over items of a list. Allow me to briefly introduce one of Python’s most interesting built in data types, the list.

1

2

3

4

mylist = ["C. temminckii", "P. marmorata ", "P. marmorata", "L. wiedii", "L. colocola", "L. pardinus", "O. manul", "P. planiceps", "P. rubiginosus ", "P. rubiginosus", "N. diardi", "P. onca", "P. leo", "P. uncia"] # um cats

# No lesson here. This is a list of cats. Be nice to cats.

Not everything has to be a lesson. Sometimes it’s just a matter of exploring your interests.

Python is probably an end goal for some people. For others its the gateway programming language into a world of systems, tools, and funfunfunctions!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

for kittycat in mylist:

kittycat.replace(" ", "+")

learn_about_exotic_and_vulnerable_cats = "https://www.google.com/search?q=" + kittycat

# What is your favorite kittycat?

# Are you a cat or dog person?

# Do you want to hear a bad cat joke?

Just kitten…

In the example above, we can create URLs from the genus and species of some cool cats (genus Felidae) by replacing the space in the strings with a ‘+’ sign to make the URI friendly to Google. By using the for keyword and iterating over the list of some Felids, we can learn about cats one at a time for the sake of near threatened or otherwise rare cats that we are kind of blessed to walk the earth with, or some s#it like that.

Cats would make better congressional leaders than the ones we have right now. I’m pawsitive.

For more flexibility, consider using the range function for ‘for’ loops. The range function ‘generates’ numbers by supplying a maximum, a minimum and a maximum, and/or step size. This is considerably more performant and memory efficient in Python than generating a list of numbers first, and checking each one for prime-ness.

What’s a generator?

A generator is a generic term for something that generates outputs, but not necessarily all at once. That would be called a ‘sploder. A generator, instead, takes inputs (fuel) and slowly converts chunks of fuel discretely and stepwise from the reservoir, producing a stream of energy.

range,yield, andgeneratorexample

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

def is_prime(x):

# Sieve

if x <= 1:

return False

for i in range(2, int(x**0.5) + 1):

if x % i == 0:

return False

return True

def prime_number_generator(num):

while True:

if is_prime(num):

yield num

num += 1

for i in range(2, 101):

# Generate a prime number from a Python generator function

prime = prime_number_generator(i)

More control flow

The break statement is useful for exiting while loops and for loops prematurely to stop infinite or excess looping than is required for functionality. The continue statement may be used when the loop iteration has the information it needs, and simply the next loop may be initiated early.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

while True:

# Check your variable

if num > my_maximum:

break

for x in range(10):

if x % 2 == 0:

# A number evenly divisible by 2 is not considered prime. We may skip the prime detection all together, saving some time.

continue

elif is_prime(x):

print("Prime number detected.\nprime number was {0}".format(x))

Object-oriented Python

Most modern programming languages (1990 and after; e.g. Python, Ruby, Java, Objective-C, Haskell, Scala and others) have some facilities for object oriented programming. Even older languages (Perl, C -> C++, PHP) have modern versions that have OOP in mind. Object oriented programming focuses on encapsulating data alongside functions that operate on such data in ‘classes’ of ‘objects.’ These objects can inherit features from parent classes and provide interfaces for the object’s user to use methods (functions specific to a class) on specific data in the object.

Python fully supports object-oriented programming (OOP) through a class interface, rather than a prototype interface (Javascript and others). Modern versions of Python (3.7+) also provide dataclasses to specify what attributes (or instance variables) an object should have. Let’s take a look at the more standard class interface.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

class Book:

def __init__(self, author, title, isbn, year, publisher, excerpt):

self.author = author

self.title = title

self.isbn = isbn

self.year = year

self.publisher = publisher

self.excerpt = excerpt

def print_excerpt(self):

"""

This is a method on the Book class that will cause the 'side-effect' of printing the excerpt string to the Python REPL.

"""

print(self.excerpt)

By using data abstraction and/or encapsulation, we keep the data close to associated functions. In this trivial example, the excerpt, a Python str, is loaded into a Book object. An instance of a Book, say, To Kill a Mockingbird, will have a specific example of an excerpt of the full text included in the ‘instance’ of the object. Calling the print_excerpt method on the instance of the Book class will print the string to the console.