Consumer technology rights and right-to-repair

Short discussion on right-to-repair and technology economics for everyday Americans

Right to repair is a political movement for consumer right to repair technological, electronic, and computer products. This is a broad category of consumer technology products ranging from automotive, agricultural, and consumer technology items; everything from tractors to cell phones. Simply put, many companies and multinational corporations are creating products that we use or interact with every day, either upstream within shipping and agricultural sectors that provide the food we eat (and then charge us for) to the gadgets we use to read, work, and entertain our families with.

What’s wrong with the way things are? An expose by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) featured the well-known Apple Genius bar, where consumers are routinely charged hundreds or thousands of dollars to repair their devices due to simple causes, humidity, beverage spills, broken screens, etc. The expose featured a well-known right-to-repair advocate and unofficial spokesperson for the movement, Louis Rossman. At the time, Rossman ran an eletronics repair shop Rossman Repair Group Inc. on 1st Ave in New York City. During the CBC investigation, an Apple technician claimed that the cost of repair for the investigators Macbook Pro would run north of 1,000 USD, possibly as high as $2,000. When the investigator took the same laptop to Rossman for a second opinion, Louis repaired the Macbook on the spot for free.

He charged the CBC journalist $0 for a trivial repair that due to Apple repair policies, would have resulted in motherboard replacements and screen replacements costing thousands of dollars.

What is right to repair?

The right to repair movement has gained traction during the 2000s and 2010s as a movement of technology professionals that are largely critical of company policies that dissuade, prohibit, or threaten legal action to consumers that repair devices against ridiculous company policies.

But I thought I owned my own device?

Well, not exactly. Major companies from John Deere, Apple, Tesla, Samsung and others often have restrictive policies for using their products and or software. “Third party” electronics repair professionals aren’t officially allowed to repair Apple products and can be sued for doing so, under breach of Terms of Service and Digital Millenium Copyright Act use of Apple device repair instruction documents.

From Wikipedia on right-to-repair:

“While initially majorly driven by automotive consumers protection agencies and the automotive after sales service industry, the discussion of establishing a right to repair not only for vehicles but for any kind of electronic product gained traction as consumer electronics such as smartphones and computers became universally available, causing broken and used electronics to become the fastest growing waste stream.[2][3] Today it’s estimated that more than half of the population of the western world has one or more used or broken electronic devices at home that are not introduced back into the market due to a lack of affordable repair.

“In addition to the consumer goods, healthcare equipment repair access made news at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when hospitals had trouble getting maintenance for some critical high-demand medical equipment, most notably ventilators.

“The pandemic has also been credited with helping to grow the right-to-repair movement since many repair shops were closed.[8] The Economist also cites the expectation that owners of products should be able to repair them as a sense of moral justice or property rights.[9] Those fighting against planned obsolescence have also taken note of when repair costs exceeds replacement costs because the companies that created the product have retained a monopoly on its repair, driving up prices.”

Why does this matter?

More Perfect Union did a recent cover story on how this affects a variety of consumers, either directly via the cost of repairs and the durability/lifespan of goods, or downstream through price increases offsetting the increased costs to workers and companies upstream. There are a variety of factors at play for the companies perpetrating these dark patterns onto their markets via DMCA copyright strikes, lawsuit threats, subscription ransoms, decreased lifespan of goods, and digital handcuffs. Most would probably say “because costs are higher” without citing specific upstream costs, development costs, or other costs they wish to pass to the consumer. And I would guess that most of the C-suite would provide highly enlightening visions to justify practices that hurt consumers: it’s probably just about money. But, that’s not so bad, right? Well… let’s see. If the iPhone model lifecycle, the nvidia graphics card generations, and a variety of other consumer products are any gauge of how things operate: you want the people to buy more of our newer gadgets. Then you have to inflate or oversell the value of these gadgets to consumers, to convince them that there’s more reasons to actually upgrade, when there really aren’t.

The famous “Thunderbolt/lightning/USB” cable “fiasco” to some, is a clever marketing gimmmick. To some of us in the technology world, it’s duplicitous. I think it smells like shit.

Sometimes, consumers are “willing” to let go of certain “freedoms” that aren’t so obvious up front. I’m sure somewhere in FutureHome’s Terms of Service, like in GM’s, there was a clause that allowed them to restructure the value proposition on things the consumer already owns. Like a car, or appliances. And, if it’s not a big deal to you that certain things aren’t repairable, or don’t technically belong to you, and can be shut off or functionality removed at any time, then don’t read on.

Reality check: some people don’t see the benefit in owning the same thing for a long time. If anything, we’re really prepared to let things go. Things that don’t work anymore, or things that other people passed on to you, stuff that’s outdated, obsolete, or have lost their charm. Or even essential features to make them interop on todays Wifi and cellular networks. Those gizmos… they just take up space, or aren’t as user friendly… but… collectively we have a big problem here. Because when we give up some common sense notions about the right of property ownership at sale, or the legal difference between owning a book and licensing it from within an app that is non-transferable, or the difference between being able to repair a laptop for a sensible amount, and turning it into one of millions of devices thrown into the landfill, then honestly we deserve what we might get.

The devil, as always, is buried in the details. If you let go of certain rights then you make room for the other party to have more. Sometimes these come in clear cut cost savings to the consumer. But they’re never made explicit. If farmers could buy one version of the tractor they could repair, and one version that they just license but have to send to John Deere, does it really matter to the farmer which way is better? Well… clearly whichever one is cheaper in the long run is one component of that calculus, and the other is what rights do we have as the licensor to change, choose, or modify terms of our component of the license agreement?. Do we have any right to choose at all? Is there only one repair shop in our town to go to, perhaps that pays large sums to the company that happens to be the only choice? Do we have any options in the market that are comparable, or provide other unrelated or additional benefits over the product we think we need?

If we have that choice, are we guaranteed to have more of such options in the future? Are companies actively trying to create business models that do not innovate and sell more useless shit instead of the least common denominator model, or better yet! One with add-ons, modularity, and options! If only…

Notable anti-consumer practices

Hewlett Packard (HP) Instant Ink subscript service

Hewlett Packard’s InstantInk subscription service has routinely bricked people's printers when their subscription expires, and continues to do so if you do not restore the subscription. People who have bought compatible ink cartridges for 100s of dollars have had their printers turned off remotely, overnight, because they failed to renew their subscription with HP’s ink cartridge program. The “conveinence” added by the subscription encourages users to order from HP’s ink store for inflated prices compared to aftermarket compatible inks. Even when replaced with compatible ink cartridges users printers refuse to print unless resubscribed. That doesn’t sound convenient in my book.

From DailyDot author Vladimir Supica:

However, the obvious downside of this verification process is that if a user attempts to print without a valid subscription—whether due to payment issues or internet disruption—the cartridges become unusable. This, as previously mentioned, occurs regardless of the actual ink level in the cartridge. And it effectively renders full cartridges inoperable due to a software feature.

Tesla’s battery replacement policies

Tesla electric cars have been plagued with a variety of anti-consumer policies and dark patterns, including insanely expensive battery repairs, software that locks cars during updates, phantom braking, expensive repairs due to undercarriage damange from road debris, damage to undercarriage components from driving through puddles in the rain, and more.

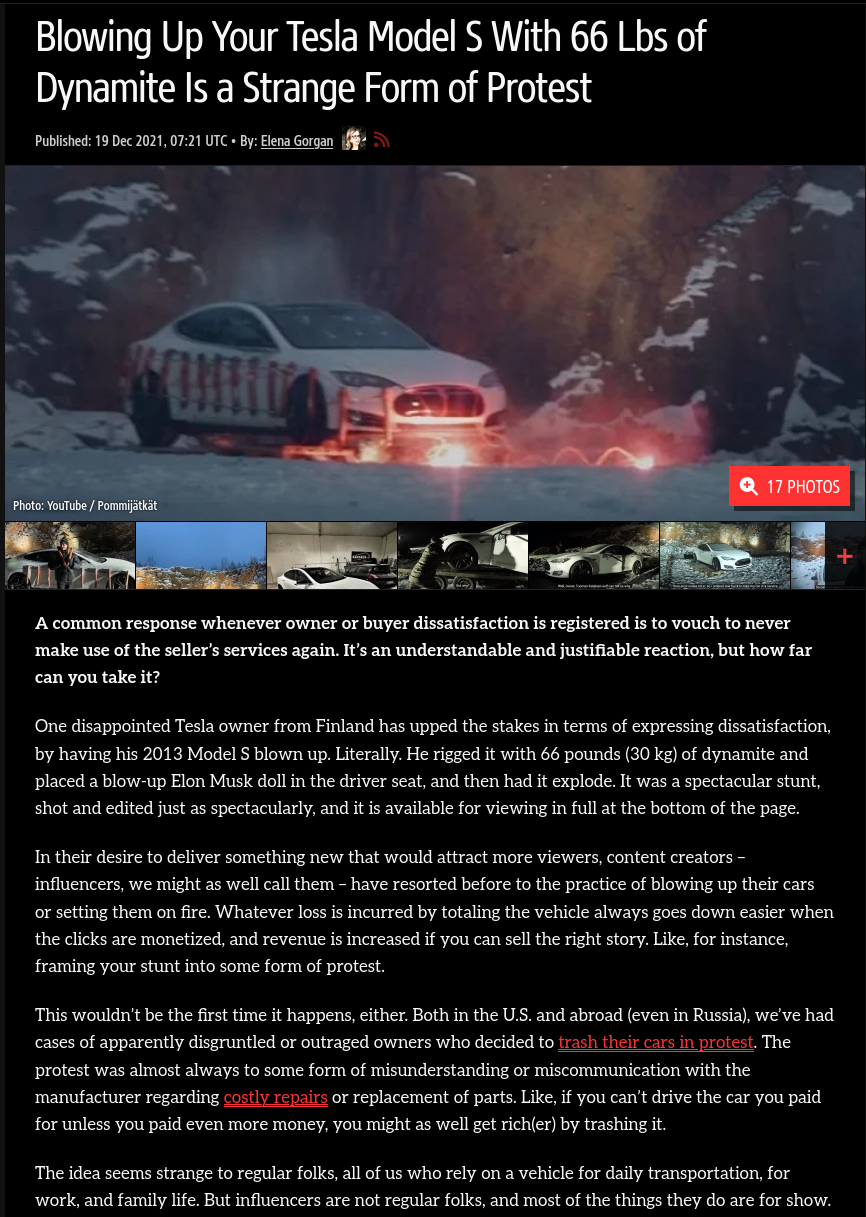

A man reportedly detonated his lightly used 2012 Tesla Model S Finnish man detonates Model S with 66 lbs of dynamite over $22k battery replacement after finding out that the cost of replacing the batteries would be $22,480. Rossman comments that although the bill for the new batteries on an older Model S should be quite expensive, it is reasonable to charge that amount for certain components like batteries, althought they shouldn’t be quite that expensive if manufacturing processes were different and not “designed to fail”. And when they fail, a $22k price tag can surely be considered a big failure.

Finnish man detonates Model S with 66 lbs of dynamite over $22k battery replacement after finding out that the cost of replacing the batteries would be $22,480. Rossman comments that although the bill for the new batteries on an older Model S should be quite expensive, it is reasonable to charge that amount for certain components like batteries, althought they shouldn’t be quite that expensive if manufacturing processes were different and not “designed to fail”. And when they fail, a $22k price tag can surely be considered a big failure.

FutureHome Smarthub app ransom

The company FutureHome, a maker of smart-home products, was declared bankrupt on May 20th this year, and decided to financially restructure the Smarthub ecosystem that affected customers using their previously purchased Smarthub compatible products to configure their smart-home integrations via FutureHome’s mobile app and cloud services. The fee was quite low, only $117 per year, which for many smart-home types was probably affordable. But when you consider what this did to the consumers, they were threatened to pay the annual fee for the app, or their entire smart-home ecosystem would become glorious paperweights, and pay for alternative services that do work. This is a classic case of a dark pattern, where something you have purchased and was functional before some point, becomes worthless at the whim of a company, its developers, lawyers, and management. But I thought I owned the electronics in my home? "Pay up buddy or we’ll turn off your climate control, lights, and bossa nova on your soundsystem". In all seriousness, it’s probably not that big of a fee for these people to swallow, but the fact that your purchases can be leveraged against you for the company to secure additional revenue is indeed a "dark pattern" in many electronic devices.