Animal fats and plant oils - costs and considerations

Healthy cooking fats - mono and poly unsaturated fats - scarcity and health considerations for common animal/plant/seed fats or oils

TODO ITEMS:

- saturated/unsaturated fats

- cholesterol molecule vs health cholesterol

- LDL/HDL lipoproteins

- triglycerides

- solubility

- energy metabolism

- uses of unsaturated fats in the human body beyond energy storage/transfer

- poly-unsaturated fats

- flash-point

- poly-unsaturated fats as redox sinks

- free radicals

- health/nutritional needs

- essential nutrients

- gut microbiome

- PUFA marketing

What is this article about

Cooking oils and fats are modestly refined animal fats or plant/seed oils that are used in commercial and domestic cooking. You’re probably familiar with two classic examples: extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) and butter. But did you know that there are several cost-competitive alternatives that may be safer and/or healthier to use in regular cooking? Read on to find out more…

So what are the key considerations when choosing a plant oil or animal fat for culinary applications? Whoa, whoa, whoa there, tiger. First we need some more context for the key questions, such as folk-wisdom about saturated fats. Then we’ll touch on some basic chemistry to discuss the health impacts and uses of poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Lastly I’ll describe some rankings we can use to address the considerations about plant oils and animal fats in cooking and health.

What do we already know

As many of us are aware, the classic choice in cooking is “butter vs extra-virgin olive oil”. Our preferences revolve around choosing a animal fat that cooks well (like butter, ghee, or lard) vs using exclusively plant oils (e.g. EVOO, avocado, canola) for cooking. And, this choice is not simple. There are multiple competing finanical interests at play, as well as regulatory, health considerations, and actual incomplete evidence regarding the health and economic impacts of the choice of a cooking fat.

We do know that in general, diets rich in saturated fats can lead to the development or increased risk of several disease categories including heart disease, stroke, thromboembolisms, and more. The damage from these can be irreversible and as such risk should be mitigated from eating diets low in processed foods, red meats, and more. Most folks have heard of such rules from our health and food regulators, and medical groups such as the American Heart Association.

So what we do know, is that low-fat and especially low saturated-fat diets may play a part in reducing risk of these diseases.

Too soon to tell: the complexity of "good" vs "bad" with saturated/unsaturated fats

[warning]: skeptic flavor follows...

Throughout this article, you'll see some definitions and descriptions of the health properties of "lipid" macromolecules.

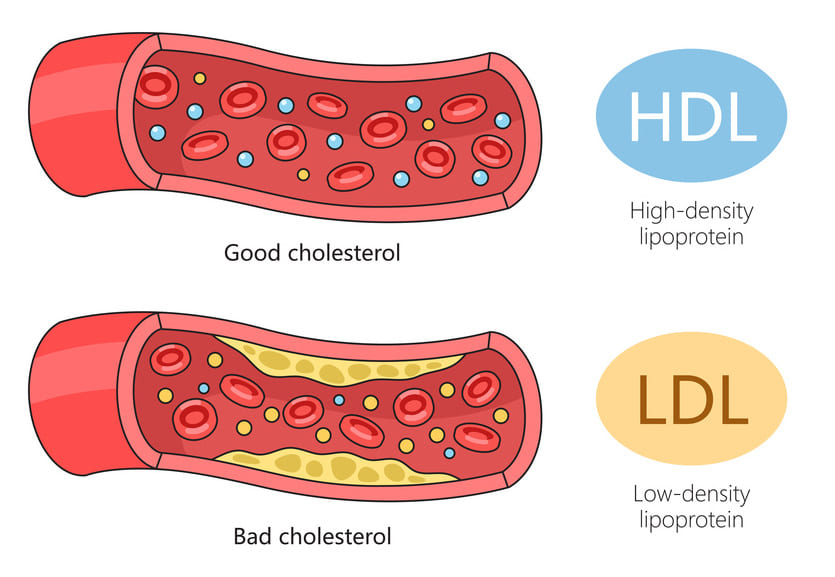

Did you know that "good" cholesterol, aka LDL lipoproteins, contain cholesterol molecules, but are actually just aggregates of fats, proteins, and other molecules into a "globule" that allows fats to be dissolved and transported in the blood?

"So what's the deal with calling it good cholesterol?"

We'll come back to that soon. First, I'll mention that there is some complexity in medical messaging in health magazines, morning shows, etc. about the health effects of Poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). There are many different kinds of poly-unsaturated fats with different availabilities in our diet. Reported results of health effects of these fats have been mixed and studies typically focus on one type of poly-unsaturated fatty acid at a time. Nutritional health studies are notoriously hard to control; variability in diet, individual lifestyle, and other factors makes controlling the health outcomes against confounding factors very difficult. As a result, it's challenging to make specific and reproducible recommendations about even a single fat or source in our diet, but it's very easy for non-experts, talk shows, and marketing language to make claims that don't have hard evidence backing those claims up.

The plant and seed oil industries have taken market share away from animal fats (butter) to increase revenue, and the category of fats known as "saturated fat" has turned into everyone's favorite scapegoat, due to some real concerns about this category from the American Heart Association. That's not a bad thing, and it's good for American Soy, it's good for other plant oils, and sustainability.

But, there is absolutely a reason to continue to use animal fats (maybe not butter per-se) beyond the fact they taste so good. Many health magazines have become unofficial press for the plant/seed oil industries, both domestic and abroad. Doctors in their columns often tout - yet inconclusive benefits of certain poly-unsaturated fats (often abbreviated as PUFAs). For example, that omega-6 PUFAs are heart healthy and consuming lots of them has benefits, while the literature often suggests that a high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio (20:1 in Western diets4) often results in elevated (bad) LDL cholesterol and lowered (good) HDL cholesterol. And to add to the confusion, some poly-unsaturated fats (some omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs) are essential nutrients for human health. Conversely? Some of the hype around omega-3 and omega-6 fats omits that many of these fats can be synthesized within the human body or its microbiome, or otherwise that many omega-6 fats are quite abundant in our diet. So is the hype around omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs worth it? It depends.

Does the advice about fats you've heard before now, seem confusing? You're not alone there. In fact, let me briefly mention my theory about how the fallacy of "naturalism" ("because it's from a plant, it must be good...") in nutrition and medicine biases the most people's view about what is "good" and "bad" in our Western diet... and it's not just that we eat red meat. The big danger to our health is eating too many fats (and the wrong kinds of fats) in general.

There's a devil in the details here. Not all plant oils are healthy. Not all fats are healthy. And the manufacturers, regulators, and health professional certainly have their work cut out for them, and certain categories (PUFAs, omega-6 which are PUFAs, etc.) contain both healthy and unhealthy fats. Finally, there is the issue of oxidative stability of saturated fat and conversely the oxidative sensitivitity of unsaturated fats.

This article is about how to navigate and understand how fats are processed and transported through your body, the health implications of these fat droplets, and how consuming a varied diet, sometimes with less plant/seed oils or fats, and/or with more stable butter/lard, may improve your health.

So... where were we again? Oh yeah: "what do we know"

In summary:

It's difficult to say definitively that one category of fat is all bad or all good. More importantly, it's important to understand how your diet is different than most peoples' diets, and how your levels of LDL/HDL or triglycerides and blood sugars are bad/good (or have unhealthy trends). Without throwing animal fats completely under the bus because they have some saturated fat, it's important to know when the rule that cooking meats with unsaturated fats (canola oil, safflower oil, corn oil, peanut oil, olive oil, etc.) turns out to play a role in aging and carcinogenesis. Hopefully by the end you'll have more questions to bring to your physicians and nutritionists about how what you eat effects your health.

Aren’t plant oils better?

Well… yes and no. They have exactly one advantage, generally speaking; plant oils are lower in saturated fat. Yes, that saturated fat, the type that clogs things inside your body.

Thank you for reading. That’s it, that’s the whole story… roll credits…

Strictly speaking, it’s a really good rule of thumb to reduce saturated fats in our diet. But, cooking with animal fats turns out to be healthy for one incredibly technical reason: avoiding oxidative byproducts, sometimes known as radical oxygen species or free radicals.

Wait… what?

Let me restate the rule of thumb the American Heart Association uses; saturated fats are mostly bad. Diets rich in saturated fat can lead to an increased risk of acute episodes that lead to heart disease as well as the more progressive clogging of certain blood-vessels, the condition referred to as atherosclerosis.

But cooking exclusively with plant/seed oils can have negative health effects too. Cooking exclusively with plant/seed oils can introduce “free radicals” or “radical oxidative species (ROS)”. Don’t believe me? Let’s dive into the chemistry later.

Challenging the rule of thumb

Many Americans can benefit from diets with low saturated fat content. Most doctors and nutritionists recommend adjustments to diet by doing the following:

- intermittent fasting

- takeout/dine out < 7 month

- caloric restriction, favoring calories earlier in the day and not at night

- substitution of red meat with poultry, fish, beans, or vegetables

- preference of fresh herbs and ground spices over sauces

- use of fresh or canned vegetables to increase fiber and slow nutrient absorption

This is fairly standard par for the course for anyone concerened with watching their weight, their blood sugar, and/or their heart health. So, naturally one wonders, what are the nutritionists and chefs doing right when it comes to food preparation, and more and more Americans are doing wrong?

Article contents

In this article I present a nuanced story concerning the 3 major categories of fats:

- Saturated fats

- Poly-unsaturated fats

- Mono-unsaturated fats

And additionally, the 2 minor categories of possible health-related unsaturated fats (not necessarily always for the better, nor even uniformly good or bad within a single category)

- omega-6 poly-unsaturated fatty acids

- omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids

Then, the core concept of oxidative stress is introduced with respect to high-temperature cooking with plant/seed oils.

And finally, the concepts of solubility of triglycerides and the poorly understood LDL/HDL cholesterol “lipo-protein” fat/protein complexes will be briefly introduced.

In summary: the core concepts of free-radical mediated organ stress, driven by high-temperature cooking with plant/seed oils instead of thermally and oxidatively stable animal fats (butter, lard, tallow) is introduced to suggest to the reader that you should consider alternatives to your preferred cooking fat/oil, and occassionally vary it, especially when cooking for longer durations and/or at high temperatures. And, the juxtaposition between saturated and poly-unsaturated fats through a lens of oxidation/reduction (redox) chemistry is provided to contextualize the choices at play in the final component of the article: a comprehensive table containing prices and saturate/unsaturated fat content of cooking oils/fats.

Let’s begin

Article goal

In this short blog entry, I would like the reader to leave with at least 6 considerations in mind regarding cooking fats/oils and their role in human health and metabolism.

- Animal fats and plant/seed oils can be healthy to cook with in small amounts, especially when incorporating fresh low-fat meats, poultry, and lots of vegetables.

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- poly-unsaturated fats (PUFA)

- health cholesterol (LDL/HDL) vs molecular cholesterol

- LDL/HDL lipoprotein cholesterol

- PUFA marketing

- Some plant/seed oils are often marketed as very healthy, but some have oxidation byproducts that you consume in steady amounts over time, putting pressure on your immune system, antioxidants, and other damage repair systems throughout your cells and body.

- flash-point

- oxidation/reduction during cooking

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- poly-unsaturated fats (PUFA)

- poly-unsaturated fats and redox chemistry

- free radicals

- PUFA marketing

- Some omega fatty-acids are thought to be important in roles beyond brain and heart health (which are oversold in non-primary literature), including immune support, endo/exo-cytosis (uptake or clearance by detox organs such as kidney/liver and intestines), cancer signaling, brain health, mood disorders, mental health, and more. Although there aren't any good rules of thumb when optimizing diets for fat health in this way, consider the presence/absence of certain categories of fatty lipid chains that neither the human body nor its microbiota may synthesize.

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- oxidation-reduction during cooking

- poly-unsaturated fats (PUFA)

- PUFA marketing

- fats, diet, and cardiology

- essential nutrients

- disputes in primary literature

- Note that cooking fats are not the only fatty component of our food. A holistic view of healthy fats must consider the lipids/fats from the protein source and whether or not the human body or oral/gut microbiota can synthesize the desired fatty lipid chain through the diet.

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- poly-unsaturated fats (PUFA)

- health/nutritional needs

- essential nutrients

- Recall4 that certain omega fatty acids are essential nutrients, meaning they must be obtained through our diet. Conversely, some monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats can be synthesized, and we don't need to consume too much of. Some of these (particularly certain poly-unsaturated fatty acids or PUFAs) may represent unnecessary oxidation targets during cooking, and can introduce free-radicals to the human body over time, which may strain organs and even cause cancer.

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- poly-unsaturated fats (PUFA)

- gut microbiome

- essential nutrients

- uses of unsaturated fats beyond energy

- I'd also like the reader to have a better understanding the difference between molecular cholesterol (a small molecule) that is part of the more common health term "cholesterol", which often refers to a ratio of low-density lipoprotein (LDL 'cholesterol') to high-density lipoprotein (HDL 'cholesterol') and the way humans transport and utilize fats (which do not dissolve well in blood), and how the VLDL/LDL/HDL components of fats dissolved in blood differ from "serum triglycerides", which are free-floating and poorly soluble fats. These components should improve the readers understanding of the way fats/lipids play a role in atherosclerosis/heart disease, stroke, lipid-sensitive pancreatitis, MASH, and more.

- saturated/unsaturated fat content

- energy metabolism

- health cholesterol (LDL/HDL) vs molecular cholesterol

- LDL/HDL lipoprotein cholesterol

- triglycerides

- solubility

Key concepts:

Key concepts:

Key concepts:

Key concepts:

Key concepts:

Key concepts:

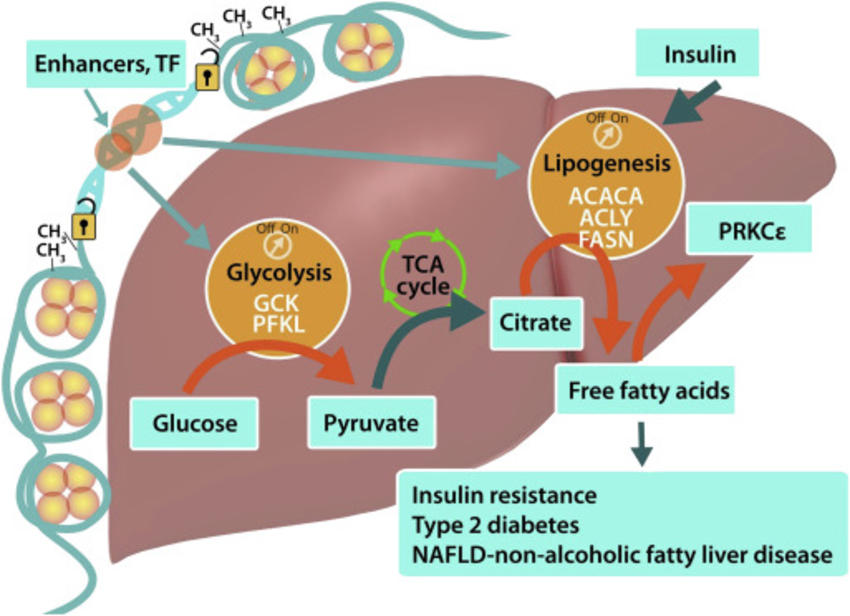

Fats and energy metabolism

Let’s discuss some biochem to understand the role of unsaturated and saturated fats in “healthy” cooking. I start with some basics of why fats are different from sugars. More importantly, why are these molecules different, how are they similar, and why does so much of nutritional science revolve around fats and so-called carbohydrates, the category to which sugar belongs.

Introduction to energy metabolism

When animals and other organisms consume energy rich molecules, such as sugar, they are consumed for two reasons. The first of which is referred to loosely as “energy needs”. The second is to create building blocks for constructing or repairing existing macromolecular structures, scaffolds, skeletons, and machines that form the basis for functioning, moving, flowing, living systems.

When animals eat and breathe, these actions combine throughout the body to “oxidize” sugar, or to break it down into almost nothing. During this oxidation, the energy stored within the sugar molecule is captured in the form of chemical “currencies” NADH and ATP. When sugar is completely consumed in this way, it combines with 6 units of oxygen gas (O2) per sugar to form water and carbon-dioxide. This first type of sugar metabolism is completely for energy and no part of the sugar molecule is retained for constructing other organic molecules. Thus, when sugar is consumed purely for energy needs, it releases its energy into the ATP/NADH cellular energy “currencies” and completely oxidizes all bonds in the sugar to form basic water and carbon dioxide.

The other primary need for sugar, is to provide building blocks for other molecules that living things require. Conveniently, the pathway for the complete breakdown of sugar into energy alone, and the pathway for breaking sugar down, just enough, for the small building blocks happen to be overlap. For the avid reader, I’d refer them to a Wikipedia article on so-called “Central carbon metabolism”.

So, for the purposes of breaking down foods into small building blocks or for the complete oxidation of all energy-containing bonds of those foods, we have a branch of metabolism referred to as “catabolism”. The opposite of breaking foods down for food or energy is called “anabolism” (as in “anabolic steroid”) and is the branch of metabolism responsible for building larger molecules, structures, and the capacities for biological growth. In a certain way, catabolism is equally responsible for the capacities for growth because it provides the building blocks for anabolism. These two branches of metabolism are complementary.

Fat: dense energy storage

Just as the economy is based on “waste not, want not” principles, the cellular/biological economy of metabolism is about resource management, efficiency, and salvage. For the sake of brevity, sugar that cells do not want to burn are first digested into smaller building blocks (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, pyruvate, and then to acetyl-CoA; see glycolysis) and then these are chained together to form a very stubborn molecule: fat. Another term for fat is “lipid” and you will see this word used interchangeably for the rest of this article.

And indeed, fat is stubborn. You see, each sugar has energy stored in chemical bonds, and some segments of the sugar molecule are very energy rich. The other parts of sugar are partially burnt off and the energy-rich parts are retained, and chained together, to form a very important molecule for living things: fat. Because the most energy dense areas are preserved during acyl-CoA polymerization (lipogenesis), the resulting fat molecule is extremely dense with energy. As a result, during exercise, you burn through your blood sugar and local glycogen reserves relatively quickly, but when that’s done, you burn fat at a very low speed.

Essentially, sugar is enjoyed when things are good. Sugars are essential parts of the diet. And, when things are going so well that energy can be spared, parts of a sugar can be “saved” in fat molecules. These fats form cellular membranes, are digested for energy, and are used as components of other molecules and physiological functions and compartments. But for now? Let’s focus on the fact that fat is an energy-rich storage molecule and doesn’t mix well in water.

Now to us, fat usually means the part of our belly that gets in the way of our pants fitting properly, or the component of the diet that plays a role in risk for heart disease. But we should think of it as just a stubbornly efficient battery. It’s energy that is stored so well, it’s like having a battery charged to 120%, and after a day of rigorous use, our battery has barely dipped below 74%.

That’s fat for you; it’s so rich and delicious, you’ll never get rid of it, willingly!

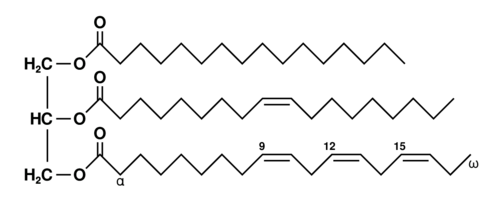

What do “saturated” and “unsaturated” mean?

Well, stricly speaking, a saturated fatty acid is completely maxed out with energy; it has no additional space to store energy on the molecule. It’s a carbon chain packed very densely, that there are no more bonds to “reduce” (the opposite of oxidize) with negatively charged electrons. As a result, saturated fats are somewhat more “energy rich” than their unsaturated fat partners, but that’s not the reason they’re unhealthy. Primarily it’s how many calories we consume in total, and not “how much energy is in a fat molecule”. Said another way: you won’t lose weight by substituting 10g of saturated fat per meal as an equal amount of unsaturated fat. It just won’t work that way. So strictly speaking saturated fat technically has more energy than unsaturated fat… but that’s not why it’s bad for you.

So what’s the more nuanced view of unsaturated fats? How are unsaturated fats “healthier” than saturated fats? Well, there are two reasons unsaturated fats can be unhealthy when used too often or at the wrong temperatures.

First, they are easily made toxic because of redox chemistry. They absorb radicals during high-temperature cooking and transfer those free-radicals to your body when they are absorbed. The solution to this first issue is of course to use saturated fats more readily for high-temperature cooking, frying, and sautéing.

Second, the ratio of different fats is concerning to many doctors, nutritionists, and scientists. This is where the USDA, FDA, medical establishment, and industry nutritional groups don’t have enough clinical evidence, have competing interests (industry vs medicine vs food safety), and generally poor consensus on what amounts of various fats are needed for Americans, and how to feasibly test and control for these things in very diverse populations, with different tolerances, traditions, and needs with respect to their choices in the kitchen. The ratio of interest sometimes mentioned is the omega-6 to omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acid ratio. Most people know this as “fish oil” advice, because salmon and other fish have more eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) than any other food source on land. We’ll get into this ratio later.

Let’s come back to saturated fats for a moment.

Okay, so the other thing you might remember about where “saturated” fats come from in the diet, is from animals. Absolutely correct, well… Anyways, animal fats are often rich in saturated fats. And that’s cool. But plant and seed oils can have as much saturated fat, or more. The first incorrect idea is that switching to margarine or seed oils will save your heart. It’s fat that is the problem, not just the type of cooking fat/oil most commonly associated with heart disease. We can thank the American Heart Association for the healthy idea, but having too much saturated fat can result from an unbalanced vegan diet too. So what gives?

Well, good things take time, and we’re gonna take as many shortcuts as we can afford to get to the more important suggestions:

- a) saturated fats cook differently

- b) poly-unsaturated fats (PUFAs) spoil differently

- c) poly-unsaturated fats are not uniformly healthier than saturated fats for heart friendly LDL/HDL balance

PUFAs have health implications, not health certainties

There is a lot of conflicting information as well as genuinely good questions about what types of fats we should have just enough of, and what types we can have too much of in our diet. The AHA believes it is always good to minimize saturated fat. And because such a huge organization has decided this rule for us, it’s reasonable to agree with. That being said, one thing the American Heart Association doesnt talk a lot about, or nearly as much as the American Cancer Society, is the concept of human beings consuming large amounts of free-radicals from cooking.

That’s where poly-unsaturated fats come in; and a bit of organic chemistry.

What are unsaturated fats?

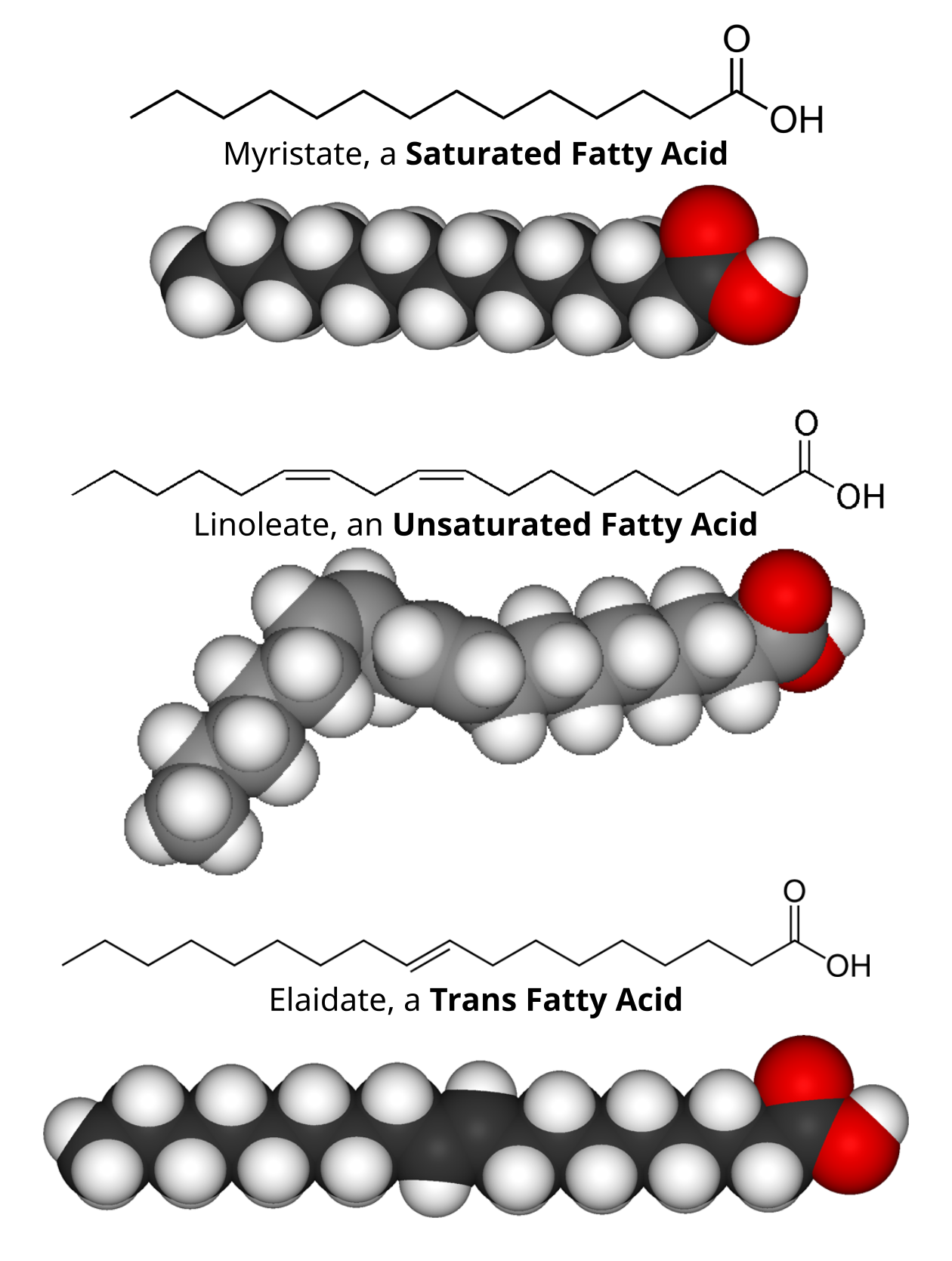

Unsaturated vs saturated fats

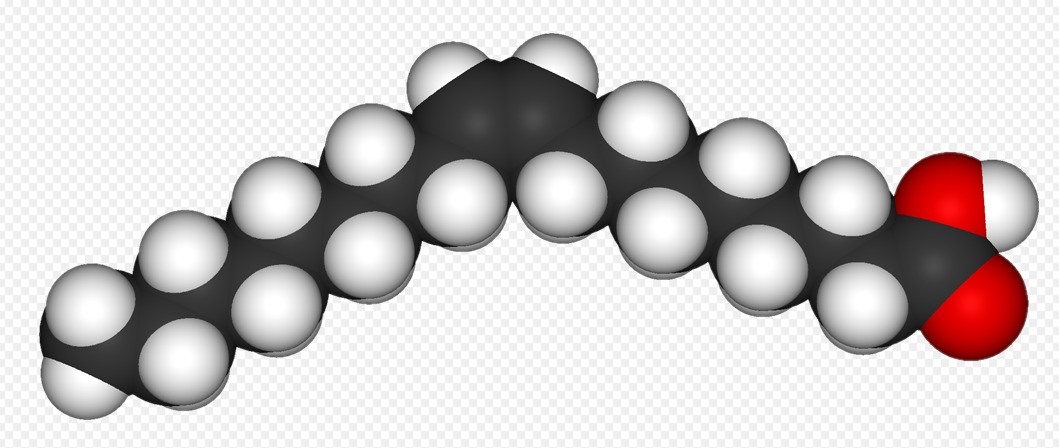

Fig. 1.a) A mono-unsaturated fatty acid chain, with a single unsaturated bond and characteristic "kink" in the fatty acid backbone.

Fig. 1.b) A comparison of 3 different types of fatty acids. On the top, is a fully "saturated" fatty acid, known as myristate. In the middle, a poly-unsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) consisting of exactly 2 unsaturated/double bonds. Finally, on the bottom is another health-risk related type of fatty-acid, known as the trans fatty acid.

Un-saturated fatty acids have two types:

- mono-unsaturated fat

- poly-unsaturated fat (PUFA)

The former have exactly one alkene bond (mono) along the fat molecule, and they are thus considered “unsaturated” with electrons. An example is shown above in figure 1.a. The second have two or more alkene (double) bonds along the backbone of the fatty acid. Often, doctors, nutritionists, and even food-industry professionals will discuss the three types of fatty acids in Fig 1.b.

Health questions about fatty acids

Saturated fatty acids

First we have the often beguiled saturated fats. Saturated fats are oily, sticky, and may contribute to the development of progressive heart disease and other disorders, such as atherosclerotic plaques. Because we’re talking about fats/lipids/oils here, and not something that dissolves well in water, saturated fats (and unsaturated fats too) often stick to the walls of blood vessels rather than float freely in the water of blood. They are often described synonymously with a related type of molecule: triglycerides. Though not the same, the abundance of both in the diet and subsequently the blood may indicate that an individual is at risk for the development of heart disease. Saturated fat and triglycerides are not the same molecule; we’ll come back to that later. The key point to remember here is that saturated fats and triglycerides have low solubility in water/blood, and tend to “stick” to the walls of blood vessels. We’ll come back to solubility later too.

Mono-unsaturated fatty acids

Not much is specifically discussed in common media about mono-unsaturated fats. However, the characteristic “kink” or bend in the fatty acid skeleton plays a structural role in why unsaturated fats are different from saturated fats to the human body, even with just a difference of a few electrons, chemically speaking. Fascinating!

Calling fats “saturated” and “unsaturated”, and referring to the amount of energy stored in the fat’s backbone, is a bit misleading. The most important difference between them is instead structural, not energetic.

The human body doesn’t care so much how “saturated” a fat is with stored energy; that’s not why saturated fat is unhealthy. Instead, it has to do with a structural difference that influences a) the oxidation tendency and b) the way the fat modulates the “stickiness” and solvation properties in different more complex compounds like triglycerides.

So in short, mono-unsaturated fatty acids are an important type of fatty acid for other reasons. They are building blocks for other compounds and otherwise are used for energy, similar to other fatty acids.

Poly-unsaturated fatty acids

Here is where there is some misinformation or just poor quality information is at play in TV, media, product labeling, and literature, amongst the fairly accurate rule of thumb from the American Heart Association on saturated fats. Now, again, their rule of thumb is very good advice generally about minimizing the amount of saturated fat consumed in the diet.

However, the American Heart Association’s page on Saturated Fats is really anemic. The take-home from their page excludes discussion of some very basic health topics:

- What are fats? What kinds of fats are there?

- What is molecular cholesterol?

- What is “good” or “bad” cholesterol?

- What are LDL/HDL lipoproteins?

- How does cholesterol relate to these LDL/HDL particles?

- What role do LDL/HDL play against each other?

- What role do LDL/HDL play in the transport of fat in the blood?

- What are triglycerides and why are they so bad?

- How do triglycerides relate to LDL/HDL and (de novo) lipogenesis in the liver?

To be honest? The issues with the Heart.org page don’t end there. There is the issue of oxidation during cooking on the development of general organ damage, including cancer. There is no discussion on how cooking fats are one component of a low-fat diet, or why high-fat diets rich in fish-oils seem to be an exception to the “low-fat” rule of thumb.

And worst of all (not specific to heart.org), there is the excessive marketing around very loose ideas about two of the sub-types of poly-unsaturated fatty acids: omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. Specific types of fat from within these groups and other sub-types happen to be essential nutrients; they can’t be synthesized by the human body and therefore must be consumed via the diet.

One of these is eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) from within the omega-3 fatty acid category. This molecule is often lauded by cardiologists and nutritionists, and is an essential (cannot be synthesized) fatty acid. Moreover, it is exceedingly rare in the human diet, driven further by reduction in viable fisheries due to climate change, overfishing, and other factors. Aquatic sources of EPA remain the largest concentrated sources of EPA outside of synthetic pharmaceutical production. As a result, there has been growing concern about the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 poly-unsaturated fatty acids in the Western diet.

The keen reader will note that this doesn’t mean that all poly-unsaturated fatty acids are essential. In fact, omega-6 fatty acids are so plentiful in the human (Western) diet, that even though we can synthesize them 1, we often do not need to because of our dietary surplus.

Before we take a deeper look at the issue of oxidation and the prevalence of unsaturated fatty oils in just cooking fats/oils, let’s take a brief look at why removing some or all animal fats from your diet might not be the best choice for your health.

3 reasons why cutting out animal fats might not be healthy:

- Animal fats are lower in unsaturated fats. Saturated fats are less likely to generate free-radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) during cooking, due to some basic redox chemistry that can be left to the reader. Cooking at high temperatures without animal fats like butter, or with plant/seed oils that have more unsaturated fats, and/or cooking for longer periods of time, may result in more oxidation byproducts in your food. These byproducts can include so-called "free-radicals" that stress or damage organs and prolonged exposure to these results in organ damage and cancer. Animal fats, in contrast, have lower percentages of unsaturated fats and, as a consequence, are more stable against oxidation at high cooking temperatures. Cooking with animal fats may result in less free-radicals consumed in the diet.

- Some plant/seed oils can be more expensive, some less so. Some have even more saturated fats than butter or tallow while some have lower saturated fat levels. Plant/seed oils aren't necessarily more or less healthy than butter, and sometimes they can just be more expensive.

- Some plant/seed oils have fatty acids that can be synthesized by the body already. One such controversial fat is called "palmitic acid" or "palmitate". Another is "linoleate". Many fats are still being investigated by doctors, food scientists, nutritionists, and oncologists about their role in human health. It isn't accurate, yet, to call plant/seed oils "healthy" because they're not "animal" fats.

Here we’ll shift from the topic of diet to the topic of heart health for a moment to explore some of the ways animals and humans transport fat/oil through the blood, even though oil and water don’t mix at room temperature. To do this, fats are often shipped from the liver through the blood with particles referred to as lipoproteins (LDL/HDL) to our tissues. Let’s start by making the distinction between molecular cholesterol and “health” cholesterol.

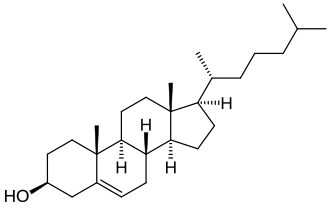

What is cholesterol?

Cholesterol is everywhere! It’s in every newspaper’s health column, every TV news segment’s morning show, every academic article on heart health… everywhere! So what is cholesterol?

Well… there’s two kinds. And it’s not “bad” and “good” cholesterol. There is molecular cholesterol (shown in Figure 2.a) and there’s “health” cholesterol (what your doctor and cardiologist will say cholesterol is). Here’s the details on the secondary type, first.

Health cholesterol (LDL/HDL)

In medical/health vernacular, the term “cholesterol” is often used in place of the term lipoprotein for simplification. Cardiologists will often refer to two kinds of cholesterol: “good” cholesterol (HDL lipoprotein ‘cholesterol’) and “bad” cholesterol (LDL lipoprotein ‘cholesterol’).

Wait, so they’re using the wrong term?

Yes, kind of.

Cardiologists are actually referring to a type of diagnostic indicator test they use, that roughly measures the amounts of different lipids/fats found in the blood.

So when they run these tests, sometimes called a “lipid panel”, they are trying to figure out how much of the fat in your blood is in high-density lipoproteins (HDL) vs low-density lipoproteins (LDL). People that have diets with high risk of heart disease tend to have different levels of LDL/HDL particles than, say, endurance athletes might have. People with excellent cardiovascular health tend to have higher/many HDL particle levels and lower/fewer LDL particles in their blood.

Here it’s important to remember to trust the advice of your physician. The trend of the HDL/LDL levels over time is often as important as the absolute value of these two “cholesterols”. And the lipid panel is one tool of many that cardiologists use to assess your heart health and the risk of developing atherosclerotic plaques, among numerous other things cardiologists monitor for.

So, I’ve described an issue in medical jargon about the term cholesterol. What cardiologists actually want to measure when they talk about your cholesterol, is how healthy your blood seems when they measure how much of the fat in your blood is in safer “good” cholesterol (HDL lipoproteins) particles vs the amount in riskier “bad” cholesterol (LDL lipoproteins).

And, as we see below, cholesterol isn’t a lipoprotein at all! It’s a molecule that is a part of lipoproteins, but this is kind of a complication with the jargon here. The cardiologists aren’t “wrong” per-se, and many heart-health indicators and medications do care about how much cholesterol you’re eating vs what’s in your blood, how much fat there is, etc.

So in short, health cholesterol is a term doctors use to refer to a balance of fat between high-density and low-density particles and may be less-likely or more-likely to form atherosclerotic plaques. Cholesterol the molecule, is a component of these particles/globules and it modulates the “stickiness” of those particles. That’s why they often talk about “good” or “bad” levels, when referring to cholesterol, to simplify things for you.

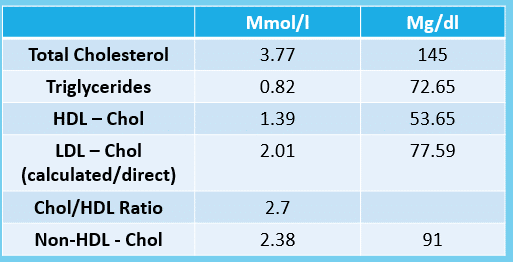

Lipid panel and LDL/HDL cholesterol

A blood-work lipid panel is a series of measurements from a patient’s blood sample with the goal of quantifying dissolved fats. Some panels may have additional readouts of “free fatty acids” and while some may refer to a specific (category) molecule called “triglycerides”. But all typically have a “total” cholesterol, and LDL/HDL lipoprotein levels.

A common test that your physician may run once a year is called a “lipid panel”. It’s a panel in the sense that there are many columns of numbers, levels of different molecules or particle counts, that they track over time. The lipid panel, is a test where they may measure/count your LDL/HDL levels, triglycerides, and other important fats in your blood.

But in our context, the important part to remember here is that lipid panels allow doctors to measure how “healthy” we are, by assessing the amounts of “good” cholesterol (high-density lipoproteins - HDL cholesterol) vs “bad” cholesterol (low-density lipoproteins - LDL cholesterol). For the sake of argument here, I’m referring to “health cholesterol” jargon and not referring to molecular cholesterol.

When the doctors run a lipid panel, they are typically interested in seeing how much of all fat in the blood is distributed between three major categories of fat:

- the “free” fats or triglycerides (usually very low concentrations)

- the “good” HDL cholesterol lipo-protein particles

- the “bad” LDL cholesterol

And the ratio of HDL to total cholesterol, or something similar to judge how much of all fat is in particles that are low/high in risk, etc.

But wait, how do fats dissolve in the blood in the first place if oil and water don’t mix?

We’ll get to that shortly. In fact, I’m gonna bury the lead on that (triglycerides) and return to our health terminology.

What are low-density (LDL) and high-density (HDL) cholesterols?

Molecular vs “health” cholesterol

Before we get to a better distinction between LDL/HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and solubility issues let’s first clarify between the cholesterol molecule (which is found in fatty membranes among its other uses), and HDL/LDL “cholesterol” (which is a misnomer because of the effect molecular cholesterol has on modulating the “stickiness” of HDL/LDL lipid-protein complexes to form atherosclerotic plaques in cardiology).

Fig 2.a) Molecular cholesterol is a structural component of membranes, a biosignaling modulator, and a precursor to some hormones and steroids. It dissolves (better) in fatty physiological layers such as cell membranes, transport vesicles, and in lipid-protein (lipoproteins) aggregates such as LDL/HDL.

Fig 2.b) LDL lipoproteins(often referred to as the "bad" cholesterol) sometimes deposit on arterial walls, leading to the accumulation of fat-protein (lipid-protein or lipoprotein) aggregates called "plaques". HDL/LDL are often referred to as "good" and "bad" cholesterol, respectively. While both particle types contain cholesterol, neither are actually cholesterol molecules.

At first glance, the nomenclature mix-up can seem confusing. Lipids (fats/oils) have been the topic of this article, and they are considered a major category of macromolecules in biochemistry adjacent fields such as medicine and nutrition (the other two macromolecule categories are proteins and carbohydrates).

As hinted earlier, if you recall from your high-school chemistry class, oil and water do not mix readily. When mixed, droplets of oil are formed along the surface and sides of a glass; this is quite similar to what happens in blood. These droplets of oil do not mix or “dissolve” in water, and instead have a tendency to cling to nearby surfaces like the walls of a blood vessel.

Oil is hydro-phobic (meaning water-fearing) and many biological molecules are partially (amphipathic) or fully hydro-phobic, instead of hydro-phillic (meaning water-loving), and instead prefer to remain in areas of the body where they don’t have to interact with water.

How does biology solve the problem of hydro-phobic, amphi-pathic, and hydro-phillic solubility in the aim of transporting fats/oils throughout the blood/body?

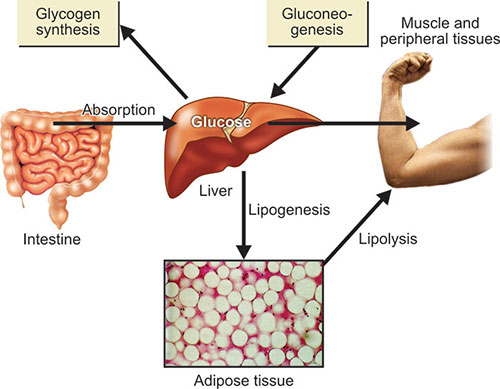

To solve this issue, let’s ask again what the human body does with extra calories absorbed from the diet.

HDL/LDL cholesterol and fat transport

What happens when someone eats too much sugar or fat?

When we consume too much sugar from our diet, our body wants to convert some of the surplus into long-term energy storage. Our extra sugar first goes to the liver, where it is broken into acetyl-CoA and is then polymerized, creating acyl-CoA. Next, these fatty-acid chains are grouped together with a glycerol, creating a triglyceride. These so-called triglycerides, though poorly soluble, are natures “least common denominator” for the storage and interconversion of fats. Then, the triglycerides are released into the blood either as free triglycerides (bad) or within LDL/HDL lipoprotein particles (good).

Because “free” fats or triglycerides don’t have good solubility in blood/water, our circulatory system would not be able to circulate the energy in fats quickly enough for animals and humans to sustain periods of prolonged activity, such as hunting, foraging, farming, reading Reddit, etc. For that purpose, the circulatory system of living things has required a work-around, hence the need for lipid-protein aggregates that have hydro-phillic outsides to interact with the water, and hydro-phobic interiors that store fats, shielded from the water in blood.

This work-around is exactly why the dissolved fats in the lipid panel are described in terms of HDL/LDL lipo-proteins and their cholesterol “spacers”, rather than in terms of the near-zero amounts of triglycerides. The lipo-proteins act as an escort for the fats through the blood, to ensure that enough energy can be delivered to the tissues. And the cholesterol in the lipo-proteins acts as a “spacer”, that creates openings for enzymes and other molecules to permeate the particle and access the fats in the interior.

Fig. 3.a: Extra sugars in the blood are converted to fat in the liver. When there is too much fat/oil in the blood, they have detrimental effects on certain metabolic disorders.

Fig. 3.b: Excess sugar is metabolized in the liver into fats (lipogenesis), which are then sent out into the blood in lipoprotein particles (HDL/LDL) to be deposited in the fat/adipose tissue or used as fuel in muscle tissue.

In short, lipo-protein particles (HDL/LDL cholesterol) are an essential part of how the human body stores and transports energy from the liver to our tissues, when we consume too many calories in the form of fat, or even as sugar.

As a result, the metabolism of the two primary macromolecules (sugar, fat) have complex feedback loops between organs, blood, and cellular systems, that impact the rate of metabolic processing through one, the other, or both sides of energy metabolism. Too much of one can impact the rate at which the liver processes the other, and imbalances are common in the West where calories are cheap and plentiful.

Now that we’ve discussed the distinction between LDL/HDL lipoproteins and their role in heart health, I hope the reader has some more context for why consuming differing amounts and types of fats and sugars can have a substantial effect on the health outcomes downstream of LDL lipoprotein maturation.

Fat solubility and “bad” cholesterol

Triglycerides

Lipid panels often measure the level of a third molecule in the blood, called the triglyceride. The triglyceride is also a lipid, consists of three (tri) fatty-acids connected via a glycerol “bridge” or head. The entire molecule is essentially hyrdo-phobic, and dissolves very poorly in the blood. The fats and triglycerides synthesized in the liver from extra calories are supposed to be sent into the blood via the lipid-protein (lipoprotein) aggregates (HDL/LDL cholesterol).

From Wikipedia:

Because fats are insoluble in water, they cannot be transported on their own in extracellular water, including blood plasma. Instead, they are surrounded by a hydrophilic external shell that functions as a transport vehicle. The role of lipoprotein particles is to transport fat molecules, such as triglycerides, phospholipids, and cholesterol within the extracellular water of the body to all the cells and tissues of the body. The proteins included in the external shell of these particles, called apolipoproteins, are synthesized and secreted into the extracellular water by both the small intestine and liver cells. The external shell also contains phospholipids and cholesterol.

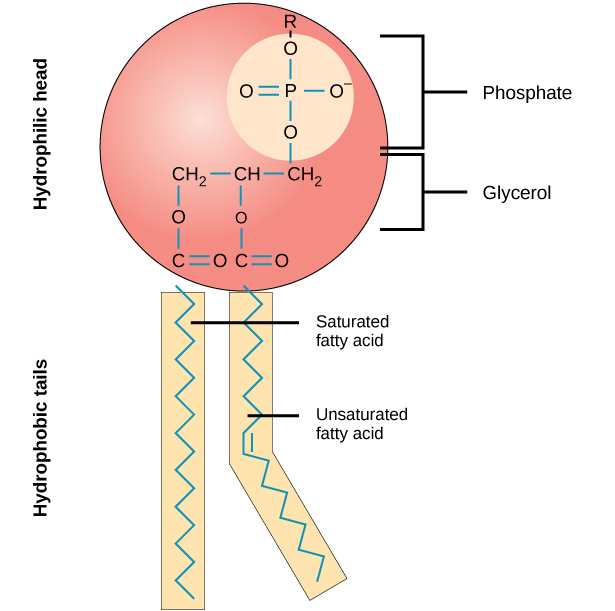

The triglyceride isn’t that special of a molecule. It’s just the least-common denominator structural intermediate of fats in the body. And when one of the three(tri) fatty acids is replaced, we have the fundamental molecule for cellular membranes: the phospho-lipid(Fig. 4.b). The phospholipid is an essential amphi-pathic (has water-loving and water-fearing sides) molecule and forms the basis of nearly every biological membrane: from the borders of tissues to the boundaries of each and every cell in the human body.

The distinction between the triglyceride and phospho-lipid is important because, although chemically speaking, the difference is very small (replace one fat with a phosphate group), the effect on compatibility with the environment of the human body is astounding. Because they are amphipathic, phospholipids can serve as fundamental components of cellular membranes, transport systems, and much more.

So on the one hand, we have a biological lingua franca for fats and long term energy storage: the triglyceride. Incredibly useful, very energy dense, very sticky. And then when we replace one of these fatty acid tails with a phosphate, we have an incredibly safe amphi-pathic molecule essential for every cell in the body: the phospholipid. What’s the problem here?

Unfortunately, biochemical systems like the liver can be leaky, and some triglycerides can even be absorbed in low-amounts from food. Some triglycerides are bound to escape the packaging in the liver into the HDL/LDL lipoprotein particles. Triglyceride levels in the blood over time do remain low due to the solubility issue, but their presence is abherent and can cause all sorts of disorders. Elevated triglycerides (in combination with LDL) increase the risk of several high-morbidity disorders including:

- Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- Coronary artery disease

- Stroke

- Type 2 diabetes melitus

- Acute pancreatitis

- Metabolic syndrome

- Non-alcholoic fatty liver disease

Because of structural reasons pointed out earlier, free triglycerides (in conjunction with high LDL cholesterol) elevate the risk of a number of diseases related to circulation and small, often delicate blood vessels that may be easily clogged by thrombo-embolism or plaque build-ups.

Now that I’ve gotten back to the topic of solubility, we can return to our discussion of saturated vs unsaturated fatty acids.

Table of cooking oils and animal fats

| Fat name | Total fat (g) | mono-unsaturated fat (g) | poly-unsaturated fat (g) | omega-3 PUFA (g) | omega-6 PUFA (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Cost (USD/qt) | Notes / properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avocado oil | 14 | 9.88 | 1.89 (±) | 0.134 | 1.75 | 1.62 | 16.39 - 39.76 | High flash point, mild taste, pricey |

| Butter | 11.5 | 3.32 | 0.43 (Ø) | 0.04 | 0.31 | 7.17 | 3.75 - 8.80 | High in saturated fat, standard for cooking |

| Canola / rapeseed | 14 | 8.76 | 3.54 (±) | 1.04 | 2.49 | 0.93 | 3.20 - 6.00 | High in PUFA, high flash point |

| Cocoa butter | 13.6 | 4.47 | 0.408 (±) | 0.395 | 0 | 8.12 | Pricey, scarce, low in PUFA | |

| Coconut oil | 11.2 | 0.86 | 0.23 (±) | 0.003 | 0.23 | 11.2 | 13.71 - 15.31 | Moderate thermal properties, low in PUFA, moderate taste bias |

| Corn oil | 14 | 3.88 | 7.41 (±) | 0.15 | 7.27 | 1.88 | 4.00 | Affordable, high flash point, very high in PUFA |

| Cottonseed | 14 | 2.49 | 7.27 (±) | 0.03 | 7.21 | 3.63 | Affordable, very high in PUFA, mild taste, | |

| EVOO | 14 | 9.58 | 1.33 (±) | 0.09 | 1.24 | 2.17 | 15.76 - 37.68 | Moderate price, fraudulent market, good flash point, moderate PUFA, high in polyphenols/antioxidants |

| Ghee | 13.9 | 4.02 | 0.52 (±) | 0.2 | 0.32 | 8.87 | 10.00 | Moderate price, low in PUFA, |

| Goose | 12.8 | 7.26 | 1.41 (Ø) | 0.06 | 1.25 | 3.55 | Scarce, moderate PUFA | |

| Grapeseed | 13.6 | 2.19 | 9.51 (±) | 0.01 | 9.47 | 1.31 | 11.99 | Affordable, low flash point, very high in PUFA |

| Lard | 12.8 | 5.79 | 1.43 (±) | 0.13 | 1.31 | 5.02 | Affordable, high flash point, moderate PUFA | |

| Macadamia | 14 | 11 | 0.5 (Ø) | 0 | 0 | 2 | Scarce, pricey, low in PUFA | |

| Margarine | 8.37 | 2.7 | 3.71 (±) | 0.38 | 3.32 | 1.69 | 6.00 | Affordable, very high in PUFA |

| Palm kernel | 13.6 | 1.55 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0 | 11.1 | Strong choice for commercial applications, affordable, very low in PUFA | |

| Peanut | 14 | 7.99 | 2.79 (±) | 0.05 | 2.76 | 2.27 | 2.99 | Affordable, moderate PUFA, high flash point |

| Red palm | 14 | 6 | 1.5 (Ø) | 0 | 0 | 6 | moderate PUFA | |

| Rice bran | 13.6 | 5.34 | 4.76 | 0.22 | 4.54 | 2.68 | mild taste, high in PUFA | |

| Safflower | 13.6 | 1.96 | 10.1 | 0 | 10.1 | 0.84 | Affordable, very high in PUFA | |

| Sesame | 13.6 | 5.4 | 5.67 (±) | 0.04 | 5.67 | 1.93 | Pricey, nutty flavor, high in PUFA | |

| Soybean | 14 | 3.09 | 7.796 | 0.956 | 0 | 2.08 | Affordable, very high in PUFA | |

| Sunflower | 14 | 2.65-7.79 | 3.95-8.94 (Ø) | 0-0.122 | 9.2 | 1.22-1.77 | 23.98 | Depending on formulation, fat composition, thermal, and nutritive properties can vary widely. Very high in PUFA |

| Tallow | 12.8 | 5.35 | 0.51 (±) | 0.08 | 0.4 | 6.37 | 10.40 | Affordable, low in PUFA |

| Shortening | 12.8 | 5.27 | 3.6 (±) | 0.24 | 3.35 | 3.2 | 10.60 | Affordable, high in PUFA |

This table uses data that has been spot-checked and collated from https://nutritionadvance.com/types-of-cooking-fats-and-oils 2, and is additionally cross-validated against the official government source known as the USDA Food Central Database (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov, 3)

Ø : - indicates USDA Food Central poly-unsaturated (PUFA) sums are more “off” (e > 0.03g), likely due to a sampling, instrumentation/methodology issue, or transcription issue between the primary source 3 and the secondary source 2 from which numbers were collated.

± : - indicates the USDA Food Central PUFA sums are off by a trivial amount (arbitrarily selected as ≤ 0.03g)

[Caution] : Cooking fats with high poly-unsaturated fats are not necessarily healthier, and oxidize at lower temperatures. They may turn rancid when stored for long periods or cooked at higher temperatures. Poly-unsaturated fats, while not saturated fats, deserve special health considerations when used for everyday cooking. Relative fat content values are in grams and normalized to 1 tbsp (13.6-14g) and the proportions of fatty acid content scale linearly. Refined olive oil was omitted from comparison to Food Central Database data collated and corrected where possible from ‘nutritionadvance’. Sunflower MUFA/PUFA oil content properties can vary by formulation. Some descriptive statistics can be found by the following URL or searching for sunflower oils using Food Central search https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-search?type=SR%20Legacy&query=sunflower

-

Lehninger, Albert L. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry: David L. Nelson, Michael M. Cox. New York: Recording for the Blind & Dyslexic, 2004. ↩︎

-

Michael Joseph, Ms. (2025, September 25). 25 types of cooking fat: Nutrition, Fatty Acids, Pros & Cons. Nutrition Advance. https://nutritionadvance.com/types-of-cooking-fats-and-oils ↩︎ ↩︎2

-

Fooddata Central Frontpage. USDA FoodData Central. (n.d.). https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ ↩︎ ↩︎2